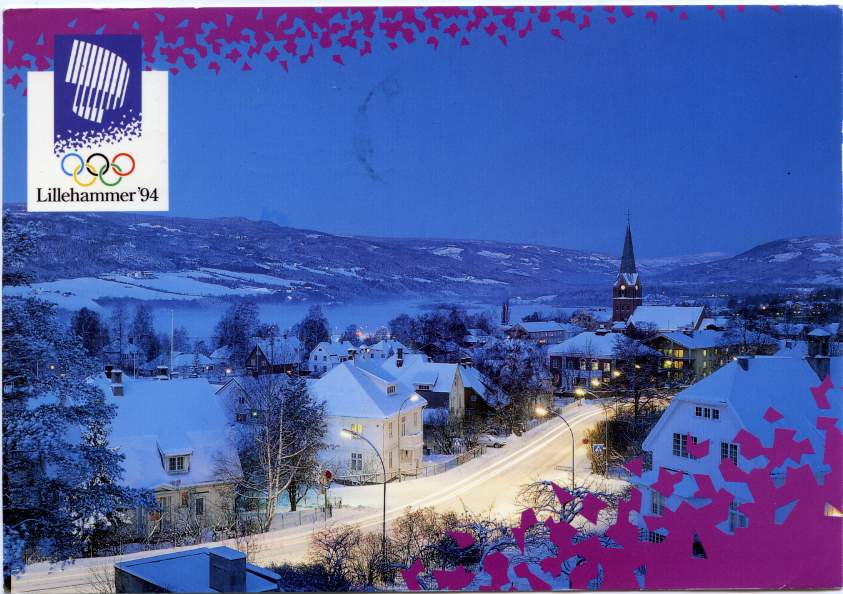

“He still has never set foot in Armenia, under whose red, blue and orange flag he proudly competed in the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway. Westford resident Joe Almasian hopes to visit his ancestral homeland someday,” reads an article published by the Lowell Sun.

“It’s on my bucket list,” says the 46-year-old father of three and youth soccer coach who plays in an Over-the-Hill Soccer League on Sunday mornings in the fall.

Never on his bucket list was driving a two-man bobsled for any country in the Winter Olympics. But their spirit of adventure and deep respect for their Armenian heritage pulled Almasian, a mechanical engineer who grew up in Sherborn, Mass.

Both were athletic. Almasian, 26 at the time, had played soccer and run track for the University of New Hampshire. Topalian, then 30, had been a hurdler in high school. They grew up participating in athletic and cultural activities within the Providence chapter of the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF).

Their talents were known to Paul Varadian, a former Providence AYF member and U.S. bobsledder with strong Olympic connections, determined to plant Armenia’s flag on the Olympic stage after independence was secured with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“The quickest entry was through the sport of bobsledding, which I was familiar with,” says Varadian, 60, who lives in Newton. “I reached out to them because they were both athletes and both nearby and they were willing to give it a shot.”

Almasian remembers being at work at EMD Millipore in Bedford (where he still works) when Varadian called sometime around Thanksgiving 1992 with his Olympic idea.

Not long after that phone call, Almasian was speeding down a bobsled run at a beginners’ camp in Calgary, where he and Topalian became properly licensed. “Because you actually need a license to drive these,” says Almasian.

In the beginning, they started each run from halfway up the track, reaching 50 miles per hour, about 30 mph slower than competition speed.

“We didn’t die, so we agreed we’d give (the Olympic quest) a try,” says Almasian.

Every Friday night thereafter during the winter of 1992-93, Almasian and Topalian drove six hours to Lake Placid, N.Y. They stayed at a motel or at the Olympic Training Center. The bobsled run was open three hours each morning on Saturday and Sunday. They borrowed 1960s-vintage sleds which they welded back together after each bumpy learning run.

They eventually hired a coach, Jim Hickey, a former U.S. bobsledder who lived in the Lake Placid area. Hickey would remain their coach through the 1994 Olympics. Almasian and Topalian shared Hickey with the Greek and American Samoan teams to spread the costs. They spent nearly $20,000 of their own money on their Olympic adventure.

“We say we had two sponsors,” says Almasian. “I sponsored Kenny, and Kenny sponsored me.”

There were no guarantees their investment would all pay off. The Olympic dream Almasian never dreamed still seemed a wild dream.

To meet Olympic qualification standards, Almasian and Topalian needed to obtain Armenian citizenship and compete in at least five international races on three different tracks over two seasons. The only two tracks in North America at that time were in Lake Placid and Calgary. So for their final qualification step they raced in St. Moritz, Switzerland not long before the Olympics.

“I think we gained one World Cup point for finishing last,” says Almasian.

Varadian handled the politicking to secure temporary Armenian citizenship for the bobsledders, which required a decree by Armenia’s then-president Levon Ter-Petrosyan. Almasian recalls it being 2 1/2 weeks before the Opening Ceremonies in Lillehammer when they got the green light.

They were nearly joined on that first-ever Armenia Olympic team by one other athlete. Arsen Harutyunyan, an Alpine skier from Armenia, fell short on a qualification technicality but carried his country’s flag at the 1994 Opening Ceremonies and skied in two future Olympics.

Marching in Lillehammer

An eight-member Armenia Olympic delegation, featuring Almasian and Topalian as its only participating athletes, marched at the Opening Ceremonies in Lillehammer. “It was held in the ski-jump area. It was freezing cold. The stands held only about 3,000 people,” recalls Varadian. “I remember Kenny saying, ‘Gee whiz, this is no big deal.'”

So Varadian pointed to a nearby television camera. “See that,” he told the two bobsledders, “that is one billion people.”

They marched not far behind “America” (countries march in alphabetically, according to the host country’s native tongue), so a glimpse of the Armenian flag was seen on CBS’ telecast to the United States.

“The sad part is we had everybody back home pumped up to watch us,” says Almasian. “I think my boot enters the screen, and then they cut away to something else.”

An Armenian reporter, serving as the team’s press attaché, arranged a press day for any reporters who might want to interview Almasian and Topalian.

“We figured at least a couple of guys would be there,” says Almasian.

The two were shocked to arrive to a room packed with media.

“We were happy to sit there and take questions,” says Almasian. “Come to find out later, though, just randomly through a scheduling process, our press conference was between Tonya Harding’s and the Italian skier Alberto Tomba’s. Those who had their front-row seats for Tonya Harding wanted to keep them for Tomba.”

But Almasian and Topalian were a story. The New York Times’ Ira Berkow wrote about the two hoping someone in Armenia, “where the electricity and gas aren’t working and people are cold in their homes and food is scarce,” knew of what they were doing and felt proud.

What began for Almasian as a quest to honor his grandparents, who escaped their homeland following the 1915 Armenian Genocide perpetrated by the Turkish government (which has denied it occurred), gained a competitive edge.

“There was the Armenian-spirit side of me, for sure,” says Almasian. “But the athlete in me wanted to be as competitive as possible within our knowledge of the sport.”

They weren’t last

In Lillehammer, Almasian and Topalian successfully completed their four bobsled runs over two days. They finished 36th, an aggregate nine minutes behind the gold medal-winning Swiss but ahead of seven other sleds. The Jamaicans, inspiration for the movie “Cool Runnings” released the year before, finished last, disqualified for an overweight sled.

“My boss had told me he’d let me take a leave of absence to go to the Olympics, but ‘you’ll have to beat the Jamaicans,'” says Almasian with a smile. “In fact, we did beat the Jamaicans … but with an asterisk.”

In the blink of an eye, as they crossed the finish line on their first run, Almasian and Topalian noticed two Armenian flags being waved above them by a group of proud Norwegian-Armenians. Almasian’s wife Kim, his fiancee at the time, flew over to Lillehammer to surprise him. Almasian’s only regret is that the return flight he booked brought him home before the Closing Ceremonies.

He has not been in a bobsled since Lillehammer 1994.

Armenia has sent teams to every Olympic Games since Almasian and Topalian paved the way. The country has won 12 medals at the Summer Games, none yet in the Winter Games.

Almasian has never received any official acknowledgment from Armenia for his Olympic service. He and Topalian after returning from Lillehammer were presented with Olympic rings made by a jeweler of Armenian descent living in Canada. Almasian kept his racing helmet and suit. He brings them out on occasion when speaking at church and civic-group functions. He also has the medallion given to all the participants in Lillehammer (along with a silver cheese slicer with the Olympic logo).

And he is proud to have been an Olympian.

“It’s fun to tell the story to people who know me, but don’t know that part of my history,” says Almasian, who has lived in Westford for 10 years. “For me, it was a proud moment.”