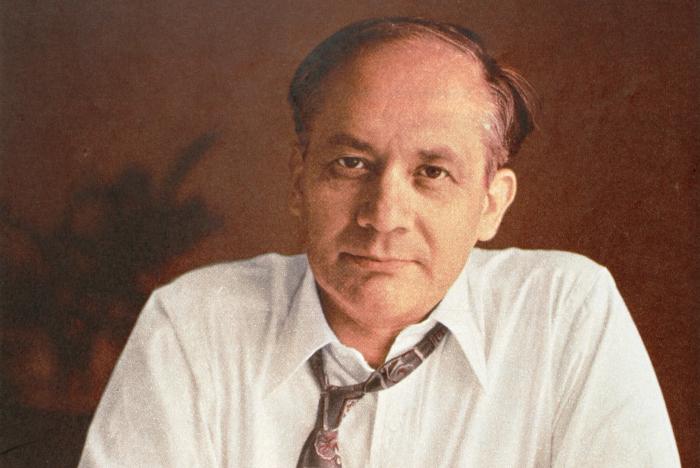

Today marks 120th birth anniversary of Raphael Lemkin, the lawyer, who coined the term “genocide” and participated in the preparation of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of December 9, 1948.

The Armenian Genocide has a special place for study in Lemkin’s extensive scientific heritage.

Raphael Lemkin was, by all accounts, obsessed with genocide long before he invented a name for it. It began when he was a teenager in Poland, as he read about the Ottoman Empire crushing its Armenian population in 1915—what is now thought to be the 20th century’s first genocide. He was shocked not just by the killing, but by the brazen way it was conducted, as if there was no concern about outside intervention or repercussion.

Lemkin went to his law professor, and was told that the Turks were the rulers, and therefore had absolute sovereignty within their borders. The citizens of each country, the professor said, were just like chickens, and the ruler was like a farmer, and he could do with them what he liked.

Many years later, in 1943, he’d construct a word—scratching out many others (ethnocide, vandalism)—to properly convey the most heinous act of human evil. The equation for “Genocide” was half “genos,” Greek for people tribe or race, and half a derivative of “caedere,” Latin for killing or destroying.

“Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?” he wondered. He decided this word would be the catalyst in which the international community would be forced to make massacres into a crime, and then use law to prosecute such acts.

By WWII, Lemkin had been peddling his ideas on genocide for more than a decade. He’d moved to the United States in the early ‘40s and watched the country standby as a mass slaughter played out across the ocean. President Roosevelt, who was eager to halt Hitler’s military advances, wasn’t going to justify a war just to stop an ethnic cleansing.

To get a resolution about genocide passed, he devised a letter-writing campaign. His strategy was to target the smallest of UN member states, writing to Haiti, Burma and others as a way to make the powers take note.

“This law shall not die, because so many human beings died to make it live,” Lemkin wrote.

Then, in 1948, it happened. Country representatives spanning the earth’s corners raised their hands to support a convention that would prevent and punish mass slaughter as a crime. “Genocide Now a World Crime,” the headlines screamed. The refugee from Eastern Europe had made his first entry into international law books.

Three years later, in 1951, it was entered officially. Today, a number of world leaders have already been charged with the crime of genocide, but more questions have surfaced: How can genocide be prevented? And how should it be stopped?

Lemkin died penniless at a bus stop in 1959, on his way to another day lobbying at the United Nations. Since then, he’s been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize seven times, and though his name is still little known, others have taken up his cause.