Why Pope Francis was right to call the Armenian massacres ‘genocide’

A century after the genocide began, Turkey still refuses to accept the truth. Yet for the sake of today’s persecuted Christians, the past must not be forgotten, Lela Gilbert writes in an article published by the Catholic Herald.

In March last year reports emerged of a nightmare unfolding in the Armenian town of Kassab in northern Syria. A horde of al-Qaeda affiliated terrorists descended on the city, forcing the Christian residents out of their ancestral homes. It was widely reported that the Turkish army had helped them or, at best, had turned a blind eye.

One of the eyewitnesses, a Kassab resident, reported that “before sunrise, we woke up to the horror of a shower of missiles and rockets falling on our town” and that thousands of extremists poured into the city, which was defended only by residents with hunting weapons.

One local man told reporters: “We had to flee only with our clothes. We couldn’t take anything, not even the most precious thing – a handful of soil from Kassab. We couldn’t take our memories.”

For the people of Kassab the new attack had a haunting historical echo, bringing back memories of one of the worst mass murders in history – the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

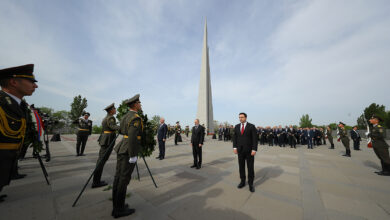

In Jerusalem’s Armenian quarter the following month, the annual commemoration of the genocide was followed by an emotional demonstration in solidarity with Kassab in front of the Turkish consulate. I watched as protesters sang, chanted and demanded the repatriation of Kassab’s populace.

The expulsion in Syria was particularly terrifying for the Armenians I spoke to, because Kassab had suffered more than a few brutal attacks in the past at the hands of the Turks. The earliest was the Adana bloodbath in 1909, in which some 160 residents lost their lives. In the Armenian genocide six years later 5,000 people from the area died. Tragically, some of the 21st-century residents who fled Kassab were the offspring of survivors; they remember their forebears’ story all too well.

On April 24, 1915, several hundred Armenian intellectuals were rounded up and later murdered by the Turkish authorities.

The word “genocide” is no exaggeration. As John Kifner wrote in the New York Times: “The University of Minnesota’s Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies has compiled figures by province and district that show there were 2,133,190 Armenians in the empire in 1914 and only about 387,800 by 1922”, following what the newspaper had described a century earlier as a “policy of extermination directed against the Christians of Asia Minor”.

After the arrest and subsequent slaughter of Armenian professors, lawyers, doctors, clergymen and other elites, widespread terror gripped the community. The Turks began house-to-house searches for weapons, on the pretext that the Christians had armed themselves for a revolt. Most homes had rifles or handguns for self-defence, and this served as sufficient excuse to arrest huge numbers of Armenian men, who were beaten, tortured and killed.

Those who survived – mostly women, children and the elderly – were given short notice to embark upon what has been described as a “concentration camp on foot”.

Informed that they were being “resettled” in remote areas for the protection of their Turkish neighbours, they were driven like animals – with whips, cudgels and at gunpoint – and offered little or no food or water. The very old and very young were the first to die along the way. More than a few mothers lost their minds watching their babies and toddlers suffer and die. There were many suicides. The eyewitness accounts and photographs are heartbreaking.

In a haunting essay in the New Yorker Raffi Khatchadourian described the brutality of the forced marches. “Whenever one of them lagged behind, a gendarme would beat her with the butt of his rifle, throwing her on her face, till she rose terrified and rejoined her companions,” he wrote. “If one lagged from sickness, she was either abandoned, alone in the wilderness, without help or comfort, to be a prey to wild beasts, or a gendarme ended her life by a bullet.”

One of the most vivid accounts comes from The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, a historical novel written in the 1930s by the Austrian Jew Franz Werfel.

His meticulously researched saga – a true story – is about a community in Musa Dagh that defied the Turkish government’s orders to be “relocated”. Instead they armed themselves with obsolete weapons and fought for their lives. Almost miraculously they survived; eventually French ships caught sight of their cross-adorned banner and rescued them.

The book is a portrait of an extraordinary place and time, as well as a tribute to human courage, resourcefulness and vision. Indeed, Forty Days of Musa Dagh is widely credited with having encouraged the embattled Jews in Polish ghettoes to resist – to the death – the Nazis who were determined to exterminate them. Not surprisingly, Franz Werfel’s books were burned by the Third Reich.

It is against this blood-smeared backdrop that today’s Armenian successors refuse to let the world forget their nation’s near-annihilation. On April 24, 2015, they will commemorate the centenary of the genocide, during which the Turkish government slaughtered not only 1.5 million Armenian Christians, but also a million Greek and Assyrian Christians.

It was very much a Christian genocide. As the German historian Michael Hesemann makes clear, these innocents were killed for explicitly religious reasons. “In the end, Armenians weren’t killed because they were Armenian, but because they were Christians,” he told the Catholic news agency Zenit. “Armenian women were told they would be spared if they converted to Islam. They were then married into Turkish households or sold in slave markets or taken as sex slaves into brothels for Turkish soldiers, but at least they survived. A whole group of Islamised crypto-Armenians was created by this offer to embrace Islam. But at least it shows that the Armenians were not killed because they were Armenians, but because they were Christians.”

Just as now, news of the massacres was reaching western audiences but few spoke up until it was too late, the exceptions being Henry Morgenthau, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and Pope Benedict XV, who had tried and failed to bring the European powers to the table. In Hesemann’s words, the pope “could not remain silent and protested three times, twice in personal letters to the Sultan and once in his speech during a consistory”.

Indeed, his attempt to stop the Armenian genocide is an impressive example of the Vatican trying everything humanly possible to save innocent victims of one of the biggest crimes in history. At the same time it shows that, frustratingly, Vatican diplomacy cannot change the minds of fanatical ideologues.

How familiar this all seems today. Through news reports, videos and documentaries, we know a lot about the intentional expulsion and extermination of the Middle East’s Christians, not only by the Islamic State (ISIS) but also such al-Qaeda affiliates as al-Nusra – who struck Kassab. These groups have practised forced conversions, extortion and murders not only in Syria, but also in Iraq’s Nineveh Plain, a Christian heartland since the second century. There some 60,000 Christian residents have been killed or expelled, their churches desecrated and all symbols of their faith and history destroyed.

Beginning in June 2014, ISIS ordered Nineveh’s Christians to leave their homes immediately. Young men who resisted ISIS’s edict of “convert, pay jizya tax or leave” were shot or worse. The elderly and infants did not fare well on the long, hot trek that followed, since most of those who fled weren’t allowed to carry food or water with them. The survivors were stripped of everything they owned. They eventually limped into Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan’s capital city.

When I visited the Christian refugees in Erbil’s Christian enclave, Ankawa, I heard the same story repeated again and again. The residents of entire Christian cities, towns and villages were given little notice – less than 24 hours, and sometimes just minutes – to leave their homes. Their possessions, and more, were stolen.

The refugees lost their personal history, their identity. They were stripped of passports, birth and baptismal certificates, diplomas, national identification papers, commercial licences and deeds of property. They handed over or left behind personal treasures like inherited jewellery, trophies, photographs and family memorabilia. The terrorists took their cars, cash, mobile phones, computers, and business and personal files. By the time they arrived in Erbil, collapsing in exhaustion in churchyards and on pavements, they had lost everything. Their Christian faith was bruised and battered. In some cases, all hope was lost.

Today in Israel, Jews ask me – some of them offspring of Holocaust survivors – “Why aren’t you people doing anything about the persecuted Christians in the Middle East?” In many ways it’s a good question. A divided global Christendom seems incapable of paying close attention, much less protesting or mobilising. They could learn much from the success of focused Jewish activism during the suppression of Soviet Jewry. One of the only countries offering asylum to the displaced Assyrian refugees has been Armenia, although the logistics of reaching the country are extremely difficult. Other Christian countries, which have the means to help, are unwilling to do so, fearful of appearing to engage in a crusade and enraging Muslim opinion.

Even official commemoration of the Armenian genocide is muted, lest it provoke a Turkish state that has always been in denial of the atrocity. Yet this refusal to recognise the first genocide of the 20th century has only made future atrocities more likely. From 1918 onwards the genocide was largely ignored in public discourse, not least by Germany, which wished to remain silent about the behaviour of its wartime ally, and its implicit guilt-by-association and silence. Such was this widespread denial that in 1939, as he planned his “Final Solution” for the Jews, Hitler notoriously said: “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

Pope Francis has not failed to speak out. Last Sunday the Holy Father referred to the 1915 mass killings as the “first genocide of the 20th century”, provoking a furious response from Turkey, which under the leadership of the increasingly Islamist President Tayyip Erdoğan refuses to recognise the genocide as a planned annihilation.

Yet to the Christians of the Middle East, for whom 1915 is not simply a historical record but a continuing nightmare, the Pope’s words will have been of great comfort. Recognition of the millions of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians who lost their lives in the 1915 genocide is not just a way of recording history but of offering hope for those suffering persecution today.

The Christian world – Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant – must persist in memorialising the Armenians and others who perished. And we must insist on recounting the brutality suffered by today’s Christians, in the Middle East and beyond, who also face expulsion and extermination. With God’s help, we will never forget. Nor will we be silent.

Lela Gilbert is co-author of Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians